Doesn't this look like the start of a Dungeons & Dragons adventure?

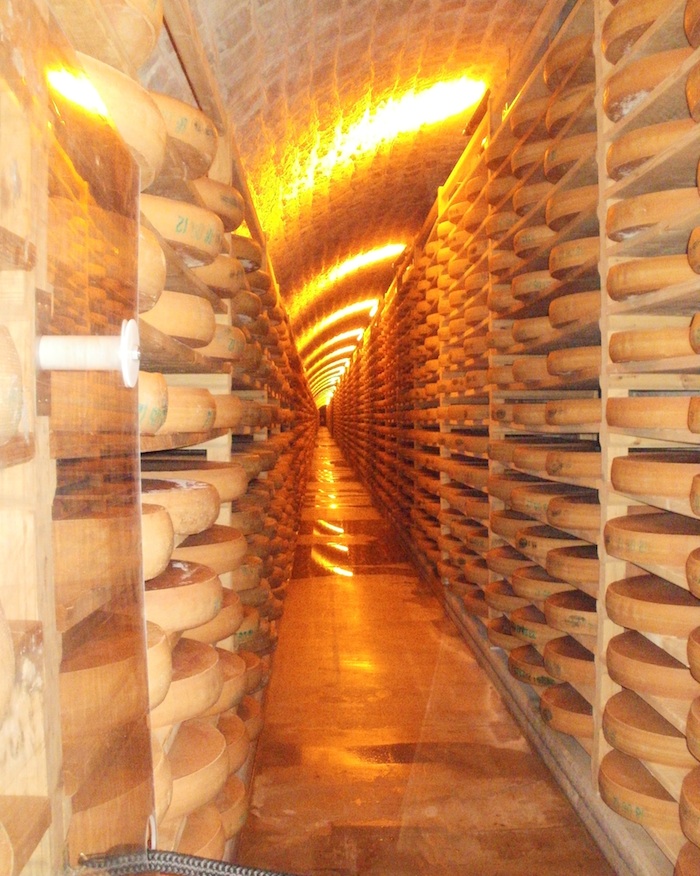

80,000 enormous wheels of Comté cheese give off a powerful stench. I can almost imagine I'm in the lair of a great smelly beast. The overpowering cloud of ammonia gas mixed with sulfurous and fermenting barnyard aromas surround me as I follow our tour guide through the underground dungeons of Juraflore. I am in east central France close to the Swiss border, in the region called Franche-Comté, at Fort des Rousses, a masterpiece of 19th century military architecture.

This is what it might smell like if 2000 horses were still stabled in the military bunker built by Napolean III to house 2500 mounted troops and protect France from the dreaded Austrian invasion. In 1998, Charles Arnaud, CEO of Juraflore Cheese, purchased a small portion of the historic fort sprawling over 230 acres. Until 1997, the enormous military complex of Fort des Rousses had been used for commando training, and Mr. Arnaud, an experienced mountaineer, served as a climbing instructor here. His family had been in the cheese business since 1907, and he noticed the deep underground galeries of the fort would make excellent cheese ripening cellars.

Charles Arnaud's crazy vision is reality 14 years later.

Charles Arnaud's crazy vision is reality 14 years later.  Now hundreds of tourists like me slip on blue plastic booties to explore the stone hallways buried under meters of stone and earth. The tour is like something from Dungeons & Dragons, and the treasure is golden cheese. The vast earthworks of the fort maintain a stable year round 7 degrees celsius temperature and the lovely arched vaults churn a slow, steady current of air, perfect for maturing Arnaud's Comté cheeses. The fort was designed to stand a year long siege, so there is plenty of water to maintain the requisite 97% humidity for the initial cheese ripening room. In all, there are three different cheese ripening rooms, each with unique temperature and humidity conditions that encourage the process of ripening Comté.

Now hundreds of tourists like me slip on blue plastic booties to explore the stone hallways buried under meters of stone and earth. The tour is like something from Dungeons & Dragons, and the treasure is golden cheese. The vast earthworks of the fort maintain a stable year round 7 degrees celsius temperature and the lovely arched vaults churn a slow, steady current of air, perfect for maturing Arnaud's Comté cheeses. The fort was designed to stand a year long siege, so there is plenty of water to maintain the requisite 97% humidity for the initial cheese ripening room. In all, there are three different cheese ripening rooms, each with unique temperature and humidity conditions that encourage the process of ripening Comté.

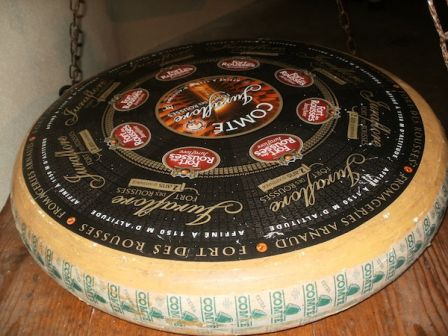

Our tour guide ushers us past a huge wall of awards won by Juraflore in various competitions, into a room displaying black and white photographs and artifacts of ancient cheese production and transport.

What looks like a wood-covered baptismal font on a stone pillar base is actually a cheese cellar used for storage before the invention of refrigeration. A cheese wagon in the center of the room has the sides of the barrels cut away to reveal cheese wheels between layers of wood and straw. Our tour guide gives us all the facts and figures in French, and answers all our questions. It's interesting and the guide is knowledgesable, but the tour remains a marketing tool for the Juraflore brand of Comté, representing only 10% of the total production of Comté cheese. There are are more than a dozen brands of comté. Our guide would have us believe Juraflore has the top quality, but I'm dubious. The Arnaud family makes some of their own cheese in Poligny, but the cheeses aging here come from over 32 different fruitières - the local name for cooperative dairies in the Jura where millk was collected and cheese made since the 13th century. The history of Jura fruitières is interesting from a historical perspective - "The cheese dairy as a patriotic example" - but also sheds light on the cultural and political values of this rural French region.

What looks like a wood-covered baptismal font on a stone pillar base is actually a cheese cellar used for storage before the invention of refrigeration. A cheese wagon in the center of the room has the sides of the barrels cut away to reveal cheese wheels between layers of wood and straw. Our tour guide gives us all the facts and figures in French, and answers all our questions. It's interesting and the guide is knowledgesable, but the tour remains a marketing tool for the Juraflore brand of Comté, representing only 10% of the total production of Comté cheese. There are are more than a dozen brands of comté. Our guide would have us believe Juraflore has the top quality, but I'm dubious. The Arnaud family makes some of their own cheese in Poligny, but the cheeses aging here come from over 32 different fruitières - the local name for cooperative dairies in the Jura where millk was collected and cheese made since the 13th century. The history of Jura fruitières is interesting from a historical perspective - "The cheese dairy as a patriotic example" - but also sheds light on the cultural and political values of this rural French region.

A wheel of Comté cheese weighs over a hundred pounds, and requires more than 150 gallons of milk. Because the cheese needed to be stored for an entire year, the wheels were made very large. But Jura farmers had small dairy herds, so one family didn't have enough milk to produce the giant cheese and a cooperative system was formed. The Jura now boasts the largest annual production of a single type of AOC cheese in all of France: 50,000 tons.

There are rows upon rows of cheeses here, stored on shelves from floor to ceiling. In the different ripening cellars the cheeses progress like candidates for Miss Universe, through a process of elimination where the best cheeses are selected for further maturation. The dungeon master, called an affineur (from the French "to make finer or better), wields his sonde, cheese probe, a metal tool with a sharp tip and hollow center he uses to extract a tiny core of cheese. The affineur uses all five senses to test and select the cheese. First he taps each disk a dozen times all over; the sound of the cheese gives information about texture and density. An extracted core is examined for color, and gently pinched and curved backwards to test viscosity and elasticity. Finally the core is sniffed and a fragment tasted before the core is stuck back into the cheese and tapped into place. The dungeon master has the final say, and scratches his initials on the side of the golden disk.

There are rows upon rows of cheeses here, stored on shelves from floor to ceiling. In the different ripening cellars the cheeses progress like candidates for Miss Universe, through a process of elimination where the best cheeses are selected for further maturation. The dungeon master, called an affineur (from the French "to make finer or better), wields his sonde, cheese probe, a metal tool with a sharp tip and hollow center he uses to extract a tiny core of cheese. The affineur uses all five senses to test and select the cheese. First he taps each disk a dozen times all over; the sound of the cheese gives information about texture and density. An extracted core is examined for color, and gently pinched and curved backwards to test viscosity and elasticity. Finally the core is sniffed and a fragment tasted before the core is stuck back into the cheese and tapped into place. The dungeon master has the final say, and scratches his initials on the side of the golden disk.

In contrast to the ancient feel of the fortress construction and old-fashioned cheese relics, seven ultra-modern robots work 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, carefully tending the cheeses. Each robot looks like a combination of a warehouse pallet truck and a miniaturized car wash. The robots gently lift each wheel of cheese on twin metal spatula arms and then whip out a round brush with a faucet poised overhead that looks just like the hubcap scrubber at a carwash. The cheese gets a thorough scrub and brine rinse, before being flipped and returned to the exact shelf location where the robot found it. Following the robots, workers toss a handful of Guerande Normandy sea salt on the freshly bathed and turned wheels.

The whole process of cheese ripening looks just as as complex and mysterious as aging wine. Whereas raw milk cheese maturation has become industrialized for certain types of cheese, that is obviously not the case for Comté. It remains both art and science, with raw materials determining how good the final product is to some extent, but just like a hedge fund investment, both skill and luck affect the final outcome. I suppose you could say that producing a really good Comté cheese is like winning a game of dungeons and dragons. There are rolls of the dice and golden treasure for the hard work of investigation and battle.

Hungry for MORE? I found an interesting blog post by David Jowett on Comté cheese affineur, Marcel Petite. David Lebovitz visited there also and gives an excellent account of the tasting and ripening process.